home // text // multi-media // misc // info

video-games musings science game-design astronomy To Infinity Ward and Beyond (the Skybox)

[edit] Oh dear Sagan. **SPOILER** alert, ‘–verbose’ alert. [/edit]

I last wrote [post expired] about Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare 2 (CoD4MW2) in regards to the controversial “No Russian” mission, and my own reaction to it (everyone is obliged to have an opinion and voice it, apparently). Allow me to continue nitpicking what is nevertheless a solid piece of game.

In the comments of that last post, my good friend Matthew pointed out the striking absence of civilians in the “Wolverines!” mission, and the dissonant chord it struck during his playthrough (read his comment and the post he links to). Which is a valid opinion to have, even though it’s provably wrong. Or, rather, it didn’t occur to me at the time, and I am thus moderately embarrassed. But, as the neo-conservatives have taught me, when someone points out something you missed, the only reaction is to start shouting louder. Actually, his comment got me thinking about a few other confusing design decisions in the game, the most astronomical of which was astronomical.

In the “Second Sun” mission, in one of the more disorienting inter-character cuts, the player suddenly takes on the role of an astronaut on the International Space Station. I say “on” the ISS, though in fact the astronaut is apparently in the midst of an EVA and is tasked, essentially, with turning slightly to the right to catch a glimpse of a nuclear missile launch (moderate spoiler). Now, right off the bat, there’s the fact that satellite intel throughout the game seems to have millimetre resolution, but when it comes to getting images of nuclear missile launches, NORAD has to dial up Astronaut Joe and ask him to tilt his head. But hey, if Infinity Ward wants to go to the next level and throw in a space mission—however briefly—I’m all for it. It’s just that I’m slightly disappointed they would do such a piss-poor job of rendering space. Odd that a triple-A title with some of the most phenomenal graphical detail to date has trouble rendering nothing.

You certainly do.

That image can serve as Exhibit A (there’s also this video which contains somewhat more in the way of spoilers and things blowing up). Let’s make like Dr. Phil and break it down.

Light Pollution

Okay, I’ll admit that at first, I wasn’t absolutely positive whether or not, from space, one could actually make out dense networks of city lights as shown in the image. Sure, more sensitive satellite equipment can put together fancy mosaics, but would the same patterns be visible to the human eye? A few quick videos from the actual ISS itself answered that one: seems that our cities are quite visible, and CoD4MW2 got at least that part right. False positive.

Milky Sneeze

That purplish glow to the right of the image? Either half of the Milky Way has disappeared, and the remaining half has increased in brightness about a thousand-fold; or the Solar System has been suddenly and violently flung into a distant nebula. There is a bright, purple, horribly low-res vomit stain across a full quadrant of the sky, so yes, Houston, there’s a smegging problem. I may have actually laughed when I saw it. I don’t think this was the intended reaction.

Oh, and if you look closely, you can see that this… thing… is actually illuminating the dark side of the Earth. Who exactly put that glLight() there? Yes, the Milky Way, in its full extent, is marvelous. It is not terrifying, nor is it purple.

Calvin’s Cosmos

At first, jumping into this scene, I couldn’t believe my eyes. Not because of the sudden, unexpected jump in perspective from a US Army Ranger to an orbiting astronaut, but rather because I just couldn’t believe the developers were trying to pass this off as outer space. I have never been more aware of a videogame’s skybox than here. The “space” textures, as mentioned above, are pathetically low-res. The seams are practically visible. The infinite black of space is rather a raver’s deep blue. I felt as though I was inside Calvin’s time-traveling box, flipped over and hastily painted on the inside. I like my outer space scenes to give an overwhelming sense of vastness. Being inside an obvious box does not do this. You’d think with all the graphical power at the developers’ disposal—the stuff that renders intense firefights and countless, highly-detailed moving objects—they could render a sphere (the Earth) and a static model (the ISS), and have enough CPU time left over to do something… anything… interesting with the depths of space. Celestial star positions are freely-available—believe me, I know—so why bother with a low-res skybox at all? Faugh.

EMP-athy

The existence of nuclear bomb-initiated electromagnetic pulses (EMPs) has been postulated and observed since at least 1945, though I credit GoldenEye with popularising the concept more recently. Now, I’m no expert when it comes to Earth’s magnetosphere, nuclear detonations, or electromagnetic interactions in general, so my feelings regarding the aforementioned nuclear blast and subsequent EMP are gut feelings at best, backed up by about 20 minutes of internets research. But lets walk through a few salient points.

Staggered power grid knockout

After the nuke is detonated, the player witnesses large segments of the Eastern seaboard’s power grid going dark, in a staggered procession emanating roughly circularly from ground zero (Washington, D.C.). My initial thoughts were that an EMP would travel at (or near enough to) the speed of light, so that all power grids within range would fail simultaneously, rather than with a visible delay. However, it seems there are several components to a nuclear EMP. The “E1” component does indeed travel at relativistic speeds, and is capable of overloading electrical circuits. In addition, though, there is a slower-moving “E3” component which bears similarities to solar-based geomagnetic storms, such as the one that disrupted the Quebec power grid in March 1989 (not the last time our lengthy transmission lines caused a few problems). Given that the E3 component can last “tens to hundreds of seconds,” and seems to be more directly associated with power grid failure, it is possible that Infinity Ward got this one right as well, and that power loss would indeed expand sequentially. But as there’s a distinct difference between the duration of a component and its actual speed, and since I really have no idea which of the E1 or E3 components would actually disrupt our electricity, I think the jury is still out on this one.

Blast radius

In 1962, the United States conducted a high-altitude EMP test code-named Starfish Prime. A warhead was detonated 400km over the Pacific Ocean. Immediately afterwards in Hawaii, 1445km away from ground zero, hundreds of streetlights shorted out, television sets malfunctioned, radio communications were disrupted (this can apparently mean only one thing—invasion!), and burglar alarms were set off. Let’s qualify this as “moderate” damage: not trivial, but certainly nowhere near total grid failure. In CoD4MW2, the warhead is detonated over Washington, D.C., and power outages seem to extend far enough South to affect videogame studies at the Savannah College of Art and Design in Savannah, Georgia. A handy Google Maps Distance Calculator pegs this distance at approximately 850km. Now, the intensity and spread of an EMP’s effects depend on a number of factors, including altitude of detonation, total yield, the local topology of Earth’s magnetic field, and so on. However, if we wave our hands a lot and assume the Washington EMP was similar to the Starfish Prime event, and that total power grid failure is an order of magnitude greater than the effects experienced in Hawaii in 1962, we can very tentatively assume that “extreme” effects such as grid failure would extend a shorter distance than the full 1445km—say, the 850km or so shown in the game—and that beyond that, equipment would sustain only moderate to trivial EMP damage (e.g., fewer lights going out). So, with a lot of ifs and assumptions, we can say that the extent of the EMP damage as shown in CoD4MW2 seems plausible. Incidentally, the same distance calculator pegs Montreal at 785km from Washington, D.C., so it looks like we, too, would lose power. Again.

Literally collateral damage

Moments after witnessing the nuclear blast, the player/astronaut and the ISS are caught in the destructive shockwave of the explosion, and, well, things go bad. Now, shock- waves require a substance in which to travel—fancy the notion! The ISS, as any fool can tell you, orbits at a mean altitude of 341km, which places it smack-dab in the middle of the thermosphere. The thermosphere is so-called because, due to the absorption of solar radiation, temperatures can soar to 2500 degrees Celsius. But importantly, “[even] though the temperature is so high, one would not feel warm in the thermosphere, because it is so near vacuum that there is not enough contact with the few atoms of gas to transfer much heat” (emphasis mine). Vacuum. Nada. Zilch. There is nothing through which a shockwave could travel, however dissipated—Astronaut Joe wouldn’t feel so much as a light breeze, much less a whirlwind that could rip apart a space station. We gave up on the idea of a cosmic æther centuries ago. And while EMP tests such as Starfish Prime did knock out or otherwise impact other satellites, these were either in the immediate vicinity of the blasts, or subsequently passed through the lingering atmospheric radiation. But developing radiation sickness doesn’t play out nearly so dramatically (or so quickly) as a full-out rock ‘n rolling nuclear shockwave.

Spatial Geometry

The problem of altitude comes up again when looking at the apparent size of the Earth as seen by Astronaut Joe. I had been under the impression that, from the ISS, the Earth takes up a massive portion of the sky/viewing sphere; in the game, however, this felt much reduced. Luckily, some kooky little ancient Greek by the name of Pythagoras Triggs went and invented trigonometry for exactly this sort of situation.

Oh yes, there’s math to be done. Pregnant women and the elderly should leave the room now. Everyone else, please brace yourselves and stand away from your monitors: I’m going to try science.

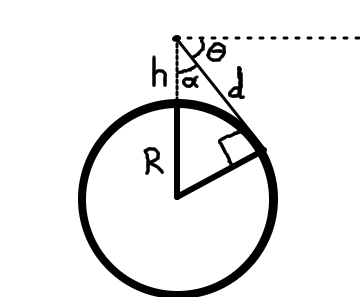

FIGURE 1: The science.

Brilliant science people have previously worked out the (more exact, apparently) formula for the distance to a point on the horizon based on altitude. Referring to the drawing above, all we need to know is R (the radius of the body in question) and h (the altitude of the observer’s eye). The distance to the horizon, d, is then defined as follows:

d = sqrt(h*h + 2Rh) (1)

I’ve used the mean value of 6371.0km for Earth’s radius (R), and the aforementioned altitude of 341km for Astronaut Joe’s viewing altitude (h), since he seems to be close enough to the ISS to make the difference negligible. Plugging these values into Equation 1 gives us a distance d of 2112.2km. This is all well and good, you say, but what does it tell us about the apparent visual size of the Earth? It tells us all we need, I respond confidently and full of aplomb. Note the angles alpha and theta in the diagram. Together, they make up a right angle of 90 degrees. Twice alpha gives the full angular size of the observed celestial body; or to put it another way, theta is the angle of depression between looking straight “ahead” and looking at the limb of the planet.

What’s more, as you’ve probably already guessed/observed, we can calculate alpha easily! d is adjacent to alpha in a right-angled triangle, and R is likewise the side opposite alpha. In trigonometric terms:

tan(alpha) = R / d alpha = atan(R / d) (2)

And just like that, we can immediately calculate alpha to be 71.7 degrees. In other words, the angular width of the Earth as seen from the ISS is 143.4 degrees, only a little bit shy of your entire field of vision in one direction (180 degrees); you can also imagine staring straight ahead and tilting your head downwards (depression angle theta) by 18.3 degrees—the resulting (very large) circle would describe the horizon of the Earth as you would see it. Compare that to the images in CoD4MW2, and you can understand the confusion: the Earth as rendered in-game seems far more distant than it should.

Of course, we can do the reverse calculation: if we assume that the angle of depression theta as shown in the game is roughly 45 degrees (which I think is fair), and since the Earth’s radius R is obviously a constant1, we can determine how high the ISS would have to be (that is, solve for h) in order to provide Astronaut Joe with the vantage point he apparently had. The derivation of the formula is left as an exercise to the reader, but to spare you the suspense, I will say that the ISS would have to be orbiting at an approximate altitude of 2639.0km. This is a far cry from achieving geostationary orbit, which requires an altitude of 35,786km, but it is nevertheless over 7.5 times higher than the ISS needs to be.

I appreciate the effort to put a memorable, distinctive space scene into a blockbuster piece of entertainment, but for a series that prides itself on gritty realism, the all-too-brief visit to outer space falls well short of the mark. Is it too much to ask for scientific accuracy in our media? Failing that, how about a little basic physical believability? Or heck, failing that, can you at least make the infinitely vast cosmic dark look less like the inside of a painted box?

Missile-aneous

Far above—too far—I mentioned a few videos taken from the ISS, which showed patterns of urban light visible on the dark side of the Earth. I want you to take 6 minutes and watch this video. It is mind-blowing, beautiful, and hypnotic. Just incredible stuff.

And one last thing. For all the controversy sparked by the “No Russian” mission; for all the acclaim heaped on the game, its production values, and its phenomenal multi-player; for all the sales records easily broken; in short, for all the hype, hyperbole, and general insanity and gossip surrounding the game, CoD4MW2 does something else very special, which no one else seems to have noticed or appreciated. When I start the game, at the first sign of anything on-screen (the Infinity Ward logo), I can press the Start button twice to get to the game itself (one more time to get to the main menu)—immediately. It has been years since I’ve been able to jump into a game as quickly as this one. No barrage of producer/developer/third-party logos (each with their own tiresome cinematic), no illegible lists of licensed APIs or incomprehensible copyright notices. Within a second of hitting “On,” I am actually able to play the game. That is huge. Just one more reason—despite my nitpicking—to take my hat off to these developers.

PS: Science!

-

This ignores the flattening of the Earth at both poles, but let’s keep things simple. ↩