home // text // multi-media // misc // info

school video-games musings computer-science game-design Down the Rabbit Hole

[warning]

Beware of spoilers for Portal, The Unfinished Swan, and King’s Quest III: To Heir is Human, for those who are still playing it. Also, this post was run with the –verbose flag.

[/warning]

I came to the realisation, about a year ago, that I owe a lot of what I’m doing to one influence: King’s Quest III: To Heir is Human.

Flash back to approximately 1989, a simpler time on a simpler PC. My videogaming leisure time was divided roughly between these three games:

-

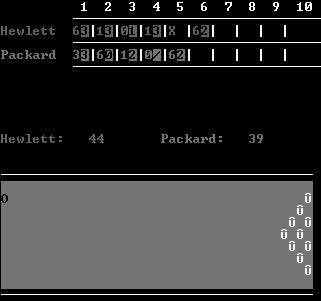

Bowling Champ, an ASCII-based bowling game which you can barely find on the Internet. Hit Space to throw your ‘0’ bowling ball at the pins; repeat several times to win.

-

Sierra Championship Boxing, a boxing game/simulation apparently more complex than I’d remembered. However, I only played it to choose the overpowering kangaroo (!!) and mash buttons repeatedly to win.

-

World Class Leader Board. If it’s all the same to you, I’d appreciate it if you could watch this video I pulled out of DOSBox:

At the age at which I was playing this, I had no idea what golf was about (this implies somewhat disingenuously that I do now); I simply mashed buttons to get the funny synthesised voice to say things.

There is a slight pattern emerging (not simply that they’re all sports games, which I only just noticed). For the most part, I played videogames haphazardly, pressing arbitrary buttons to make flashy things happen. I never understood that any of these things might have a goal—one of the reasons, incidentally, why I only beat Super Mario Bros. (NES) in 20061.

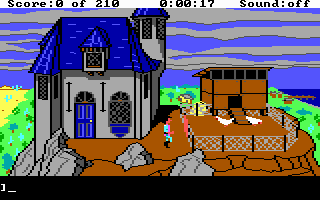

I played King’s Quest III in the same mindset. For those unfamiliar with the game, you start off as the young slave Gwydion coming of age in the service of Manannan, an evil wizard. The scene is set with Gwydion (and the player) performing a variety of domestic tasks: FEED CHICKENS, SWEEP KITCHEN, EMPTY CHAMBER POT. I imagine Ken and Roberta Williams, the game’s designers, had it in mind that these menial chores would serve as a dramatic counterpoint to the upcoming adventures, or at the very least encourage the player to work towards Gwydion’s eventual escape. Oddly enough, it had roughly the opposite effect on me: I had no real experience in goal- or narrative-driven videogames, and enjoyed the resulting animations so much, that I spent all of my time wandering around Manannan’s mansion, toying around in the various rooms, sweeping floors and emptying chamber pots.

One day, I was watching my older brother play KQIII. He either had a much higher capacity for abstract thought, or was extremely bored with feeding chickens (the novelty was slowly being lost even on me), but he did something absurd: he left Manannan’s mansion. Navigating a steep, pixel-precise cliff face, he climbed down the treacherous mountain and was (for the moment) free. I was shocked. My conception of the game had been effectively a butlering simulation with an abusive master; suddenly, the possibilities were enormous. There were at least eight exciting new screens to explore, and there was so much more stuff to do.

This was what I’ve come to call my first “down the rabbit hole” moment, a sudden, drastic, and fairly wondrous awakening to a new realm of exploration and possibility. This was the first time that I actually began to grok the potential of videogames, and as I’ve stated above, it was probably the earliest experience that would come to have an impact on my present interests. To quote Q in one of the best television episodes of all time: “For that one fraction of a second, you were open to options you had never considered.” But before I dig more deeply into that process, let me digress briefly to point out two other, more recent “down the rabbit hole” moments that are worth mention—if not for the rarity with which one finds such things these days, then for the quality of their execution.

Portal

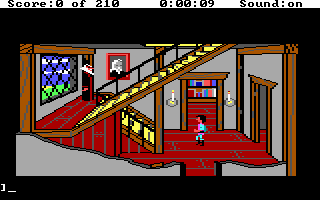

Granted, the game isn’t lacking for praise, but one element stands out for me far beyond the rest. Obviously, I couldn’t help but enjoy the game’s design and aesthetic, as well as GLaDOS’ fantastically-written and -voiced dialogue2. But my initial reaction was that it was “just” a game about a new mechanic (creating and passing through portals), just a collection of puzzles featuring a somewhat sadistic cheerleader. And then I hit Chamber 16.

This Chamber throws cheerful turrets at the player for the first time, training them to beware the red targeting beams.

You can barely see it in the above photo, but down the hallway, where the corridor jogs to the right, a weighted cube seems to hover slightly askew, breaking the geometric precision of the Chamber’s halls (go read what smart people have to say about guiding the player’s eye). Of course, it becomes more apparent when one moves closer:

Ducking into this recess to examine the turret situation, the player basically stumbles over the Rat Man’s den—the first glimpse of a reality beyond GLaDOS and portal-puzzles…

This was my defining moment of Portal, the Rat Man Reveal3. The game was no longer a challenging, somewhat tongue-in-cheek puzzler; there was suddenly a new sense of urgency, an emotional investment in the game’s two human characters (one of whom is never actually seen), and a very clear goal: escape. I felt the Rat Man’s isolation and desperation, and realised it was my own. This was down the rabbit hole into a very, very bad place.

The Unfinished Swan

A few months back, I attended the 2009 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, and wrote about this game. All of the games in the Experimental Game Design session (of which TUS was a part) were fascinating in their own right, but this one remains my runaway favourite. Go ahead and watch the video:

Once again, it starts out simply enough. You throw paint, and an environment is revealed. Then at 0:51, the rug is pulled out from under your feet, and the game takes on a completely different meaning. I may have gasped audibly when I saw this during the game’s demo at GDC.

The Finding-out of Things

I consider all of these examples—KQIII, Portal, and The Unfinished Swan—to be “down the rabbit hole” moments. I’ll admit that they may be fairly personal (my KQIII experience certainly was), but I’d like to think they’re not totally unique; hopefully, some of you reader-folk have had the pleasure of such experiences. At the same time, I feel that the simple act of world exploration—growing in popularity with the ever-more-popular open-world games—nicely represents the process in miniature.

I’m one of those players that tends to try to completely uncover a game’s virtual world before “getting down to business.” Fuzzy fog-of-war or blank areas on a map tend to frustrate me. In terms of Richard A. Bartle’s taxonomy, I am a “Spade,” or an explorer. Although Bartle assigns a specific class to this type of behaviour, I think it’s present in just about any gamer, or any audience in general. The temptation to find out what’s on the other side of a mountain or where a river leads is always very real. Answering those questions may not have the full psychological “oomph” of a down-the-rabbit-hole moment, but the process nearly always opens up a new vista or a new possibility to explore, which is in itself a reward and an incentive for further progress.

J.J. Abrams—creative and/or directorial force behind Lost, Mission: Impossible 3, Cloverfield, Star Trek, etc.—spoke in a semi-recent TED talk, and a much more recent WIRED magazine editorial, about the power of mystery to keep an audience engaged, and the joy experienced in the actual process of discovery. This is the attraction provided by the exploration of strange new worlds: every mountaintop or dungeon or abandoned building presents a new mystery. I always point out that people generally seem to enjoy The Fellowship of the Ring more so than the other books in the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Told basically from the point of view of hobbits leaving the Shire for the first time in their lives, it carries both them and the reader through wild and unknown territory (literally and figuratively). The other books are excellent, but they lack the exploratory draw of Fellowship. Likewise, games like World of Warcraft can keep players addicted to incessant grinding provided there is some sort of growth or exploration. Players reaching the highest class echelons, however, seem to require a constant influx of new collectibles in order to keep them interested. In both cases, it seems to be the continual process of mystery, discovery, and growth that keeps people engaged.

The Making of Things to be Finded-Out

So, I started off talking about KQIII. Falling down the rabbit hole (read: a cliff) into the wider, wilder setting of Daventry was the kick that turned the casual world-explorer’s curiosity into a full-blown mania. I am perhaps only a “spade” out of a fear that, once again, I’ll miss out on the major portion of a game’s experience because I am too busy emptying chamber pots. But the impulse is undeniable.

Watching (and reveling) as videogame worlds became larger and more intricate, I began to realise that such scale would be daunting for many game developers. I also soon learned that the methods existed to shift the burden of world creation to computers. But not only can procedural content generation free up the budgets of game development companies; it also has the potential to create practically limitless worlds for players to explore. I would love to see a game where, at the press of a button, players could be dropped into a completely fresh landscape and start the process of discovery all over again. The techniques exist, in theory. It’s a direction I’m sure games will head in, and because of my childish mis-steps in King’s Quest III, I want to try to help make it happen.

To quote Q once more: “That is the exploration that awaits you.”

See you out there.

-

[Note from 2023-09-11]: A derelict link to my 2006-11-05 post, “Another Castle”, in which I emerged from a recently-inundated basement to beat SMB. Pics available: 1, 2, 3 ↩

-

Yes, this form of suspended hyphen is apparently valid. ↩

-

I suppose I might have gathered something was amiss from all the empty observation windows and rooms. What can I say; I sometimes overlook those things that are lacking in favour of those things that are presented to me. ↩