home // text // multi-media // misc // info

video-games musings astronomy frustration Aperture (Bad) Science

I got up at 4:30 this morning because Portal 2 got astronomy wrong.

More accurately, I was woken at around 3:00 by torrential rains and more than one thunderclap; then, as the storm passed and I was wide awake, I took to reading more of Green Mars (which, incidentally, is still bloody fantastic); then I put my head down and tried to force myself back to sleep, but succeeded only in thinking about video games. And then, at 4:30 this morning, I got out of bed because Portal 2 got astronomy wrong.

It is (morally) necessary and (literally) sufficient to say that this post contains some moderate (read: extreme) narrative spoilers, and so I provide the following video free of charge as a convenient internet boundary. All you cats who haven’t finished the game, make like Indiana Jones and do not cross the seal with the Holy Grail/your web browser:

Nooo, Dr. Schneider! There are Portal 2 spoilers down there!

You’ve been warned (and delighted by another’s slapstick misfortune!).

So, by now you’ve all read my Bad Astronomer-inspired deconstructions of Modern Warfare 2, Mass Effect, and Moonbase Alpha. You’ve laughed, you’ve cried a little, you’ve cried while laughing over brandy and a roaring fireplace screensaver. Well, fire up the brandy and brandy up the fire again! We’ve got another visitor.

Good-natured Preface

I liked Portal 2.

Knives out

There are a fair number of criticisms to level at the game: that the original Portal was too perfect to require/deserve a sequel; that the new game broke down into a series of “Find-the-portalable-surface” puzzles; that the {repulsion|propulsion|conversion} gels felt mechanically tacked-on; that the writing was entirely too self-aware. It’s all been said elsewhere on angrily-harried keyboards, and I’m certain a quick Lycos will find you a bundle.

My own complaints are (seemingly) unique, however. I’d had a feeling—as soon as I saw the “Lunacy” achievement title and description—that something wild and astronomical was going to happen in-game (maybe another trip to Xen! No, no not that thing.) and that I might have a chance to get scientifically chuffed once again.

Indeed.

Previously…

Now, Portal 2 has rather a memorable ending sequence:

As well as a somewhat more subdued and touching epilogue:

At first, I only took (cold and objective) offense at the latter video, but a brainstorm during the rainstorm this morning unlocked a few more points about the former video as well, as we shall soon see.

In space, no one can hear you sigh dejectedly

Sound in space. My white whale.

In that second video, I suppose I’d be willing to believe we’re eavesdropping on some form of digital communication channel direct from Wheatley. But then, that wouldn’t explain why we hear the clanking of his mechanical pupil. Or why the Space Core’s voice attenuates as a function of distance-to-camera. And seems to echo? Against a physical object? In space?

Sigh. Well, at this point it’s not even worth mentioning anymore; in fact, it’s more noteworthy when games or movies or television actually portray the physical reality of space.

“Hey, did you see that new movie? The sky was blue in the outdoor scenes! I love it when movies have that kind of scientific realism!”

Bollocks.

And now in a circular motion, rub it

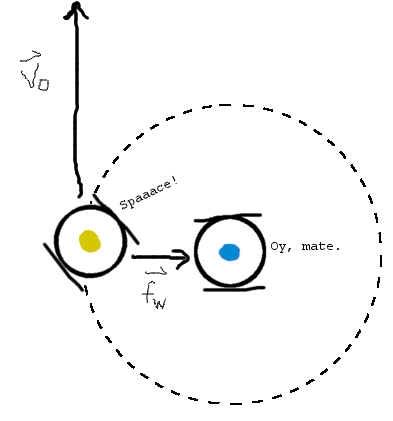

The Epilogue furthermore shows a humbled Wheatley dreaming of forgiveness, whilst the Space Core orbits happily around him. There is a word I do not like in there. It is not “whilst”—I frigging love that word. The word in question is “orbits.” Look at this drawing:

No, REALLY look at it. I literally spent hours.

Both cores are ejected vertically “out” of the Moon with roughly the same velocity. Somehow, the Epilogue implies, Wheatley has captured the Space Core and made it a satellite. This necessarily means that Wheatley is exerting a force fw on the Space Core—be it a passive gravitational force, or an active and as-yet-undisclosed Physical Attractor Beam in Space-Time (or PABST Blue-Ribbon). If the latter, well, one might assume he could use these gravitationally-manipulative powers of his to eventually propel or pull himself to Earth; but then it would beg the question as to why he wouldn’t have used them in any number of situations during the game itself, and heck, I’m going for consistency here.

On the other hand, Wheatley might exert a passive gravitational pull on the Space Core—in which case, it should be child’s play to calculate his mass! Indeed, various formulae exist for calculating orbital speed in a two-body system:

Equations for orbital speed (Vo) of one mass (m1 – the Space Core) around another (m2 – Wheatley) at a radius of r. G represents the gravitational constant; in Equation (2), the central mass being orbited (M – again, Wheatley) dominates the system, making m1 negligible and simplifying Equation (1).

Now bear with me, I’m about to make a lot of asses out of u and me: first and foremost, that we have the situation in Equation (2), where Wheatley’s mass is much, much larger than the Space Core’s. In the Epilogue video, the Space Core takes approximately 9 seconds to complete one orbit of Wheatley. If we also assume a perfectly circular orbit (ha!) with a radius of… what looks like an average of two metres, we can calculate that the Space Core is moving at around Vo = 2PI * 2 / 9 = 1.396m/s. With the values for Vo, r, and G known (the latter is a quick web lookup), we can plug the numbers into Equation (2) and solve for M.

As depicted, Wheatley therefore has a mass of 58,408,991,458.115kg. Assuming his volume is approximately that of an average basketball (0.00710421831 cubic meters), then his density is a significant fraction of that inside a neutron star. Which makes him rather light on his feet (rail?), all things considered.

Phase Change

The question outlined above of orbiting bodies was the first and most glaring astronomical error I noticed in Portal 2’s endgame, and I was prepared in fact to just let it go and move on. But lo! it was just this morning that a final and damning thought occurred, and was soon confirmed with Internet Research (read: the timeslip between Twitter and Facebook refreshes). How remiss I would have been not to trouble you with it all.

In the climactic moment of the Battle with Wheatley, a hole is torn in the roof of the Aperture facility, revealing our dearly beloved Luna:

I won’t calculate the size of impactor that would be required to make a flash of light on the Moon as large as that in the game, but, well, you know: exercises for the reader.

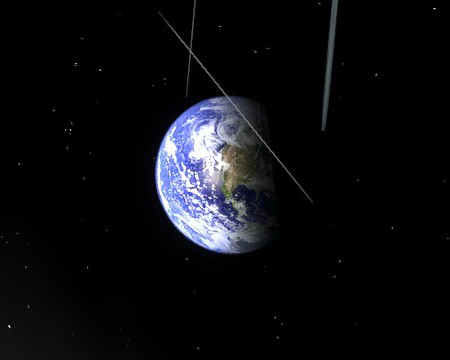

And once on the other side of the Lunar portal, the player has a moment to reflect on the Earth, down below:

Exercise 2: What should be the apparent radius of the Earth as seen from Luna?

A beautiful moment, admittedly, and it took me about a month before I noticed a rather serious and basic problem of geometric configuration: both the Earth and the Moon are in their respective gibbous phases.

For accuracy’s sake, I’ll make a little digression. Aperture Science (at least the Enrichment Center) is said to be located somewhere in Upper Michigan. As this is in the Earth’s Northern hemisphere, that makes the Moon we see in the game a waxing gibbous moon—getting larger and larger, almost Full and at the point of opposition with the Sun (as viewed from Earth). On the other hand, if the game had taken place in the Southern hemisphere, this would have been a waning gibbous Moon—shrinking on its way to a New Moon.

In either case, an important and rather obvious fact must be true: the gibbous Moon must be somewhat “behind” the Earth as seen from the Sun. If that is the case, then another fact must necessarily also be true: from every position on the Moon, the Earth would be seen only as a very thin crescent [Ed.– omg so so so so so gorgeous!] Of course, the reverse is also true: if Earth appears gibbous from Luna, then the latter would appear only as a crescent to an observer on the former.

If we consider it from another perspective (was that a pun? I can’t even tell anymore): the only configuration in which two bodies can appear gibbous to each other is when they are on opposite sides of the Sun (though not in opposition). This is, naturally, quite possible when we compare Earth and any other planet in our lovely little system; on the other hand, it will never happen to Luna until they pry her from my cold, dead gravitational well.

As I mentioned, it was an error subtle enough to go a month without my noticing it. But while Mass Effect easily takes home the prize for most embarrassingly-flawed depiction of Earth from Luna, I’d say Valve comes in at a tight second place here.

Related: Michigan seems to be right around the Earth’s (overly linear) terminator, though not yet in complete darkness. Why, then, does the Moon appear, from the Enrichment Center, to be set against the backdrop of full night? It’s a subjective call, I suppose, but worth investigating.

Lunar Litter

Bon, we’re almost done here.

Looking back at that picture of Luna, the visible flash of light places the portal’s terminal point somewhere near Menelaus crater, between Mare Serenitatis and Mare Tranquilitatis. The Half-Life wiki beat me to the punch here, pointing out that none of the Apollo missions landed nearby, much less any of the three that carried a Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRVs, present on Apollos 15 through 17) as seen in the full panorama of that scene.

We could nevertheless, for the sake of argument, claim that the flash of light came instead from the portal’s transient interaction with Earth’s atmosphere, and assume that Chell does emerge at one of the three given Apollo landing sites. The Half-Life wiki discounts the possibility of Apollo 15, given that the American flag was knocked over during the return-trip launch of the Lunar Module (LM) ascent stage. What other clues can we gather from the enlarged screenshot?

Well, visible very close by and to the right of the LM descent stage is the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiements Package (ALSEP). From left-to-right we see three components: the Radioisotope Thermal Generator (RTG), (most likely) the Active Seismic Experiment (ASE), and the Central (computing) Station. Interesting attention to detail!

Unfortunately, if Wikipedia can be trusted (and I cannae ken a SINGLE REASON why it should not), the ALSEP was approximately 110m from the Apollo 15 LM, and 95m and 185m from Apollos 16 and 17, respectively. That’s a good distance away, where the game makes it look like only a small step and a sizeable leap.

Finally, I haven’t found any traverse maps of the Apollo landing sites, and so can’t verify the final resting places of the three LRVs relative to their Apollo LMs. But I’d reckon they’re much, much further from the descent stage than depicted in-game (where it’s shown as… roughly 20-30 metres). There is the famous video of Apollo 17’s launch from the Moon…

…but even then, it seems as though the camera is tightly zoomed in to begin with, with the LRV parked a generous distance away. It makes sense to me: I’d want my launch zone to be as clear of heavy/sensitive machinery as possible. But it brings us no closer to identifying the in-game Apollo landing site.

Reductio ad absurdum

I’ll say it again: I thoroughly enjoyed Portal 2, and appreciate the unique twist they threw into the finale. I mean, you have to respect a company that takes the time to model and place the ALSEP just because they are gangstar like that.

So if they’re willing to forgive my pedantic pick-nittering, I’ll gladly forgive them their flagrant disregard for basic science fact.

We’re cool, Valve. We’re cool.

QED.